Ingmar Bergman’s centennial is on July 14th, and while Janus Films has been touring the country with a massive retrospective of one of the most prolific and influential cinematic auteurs, The Criterion Collection has announced that the international jubilee will continue all year long with the November 20th release of the most comprehensive collection of Bergman’s cinema ever released on home video.

From Criterion:

The struggles of faith and morality, the nature of dreams, and the agonies and ecstasies of human relationships—Bergman explored these subjects in films ranging from comedies whose lightness and complexity belie their brooding hearts to groundbreaking formal experiments and excruciatingly intimate explorations of family life.

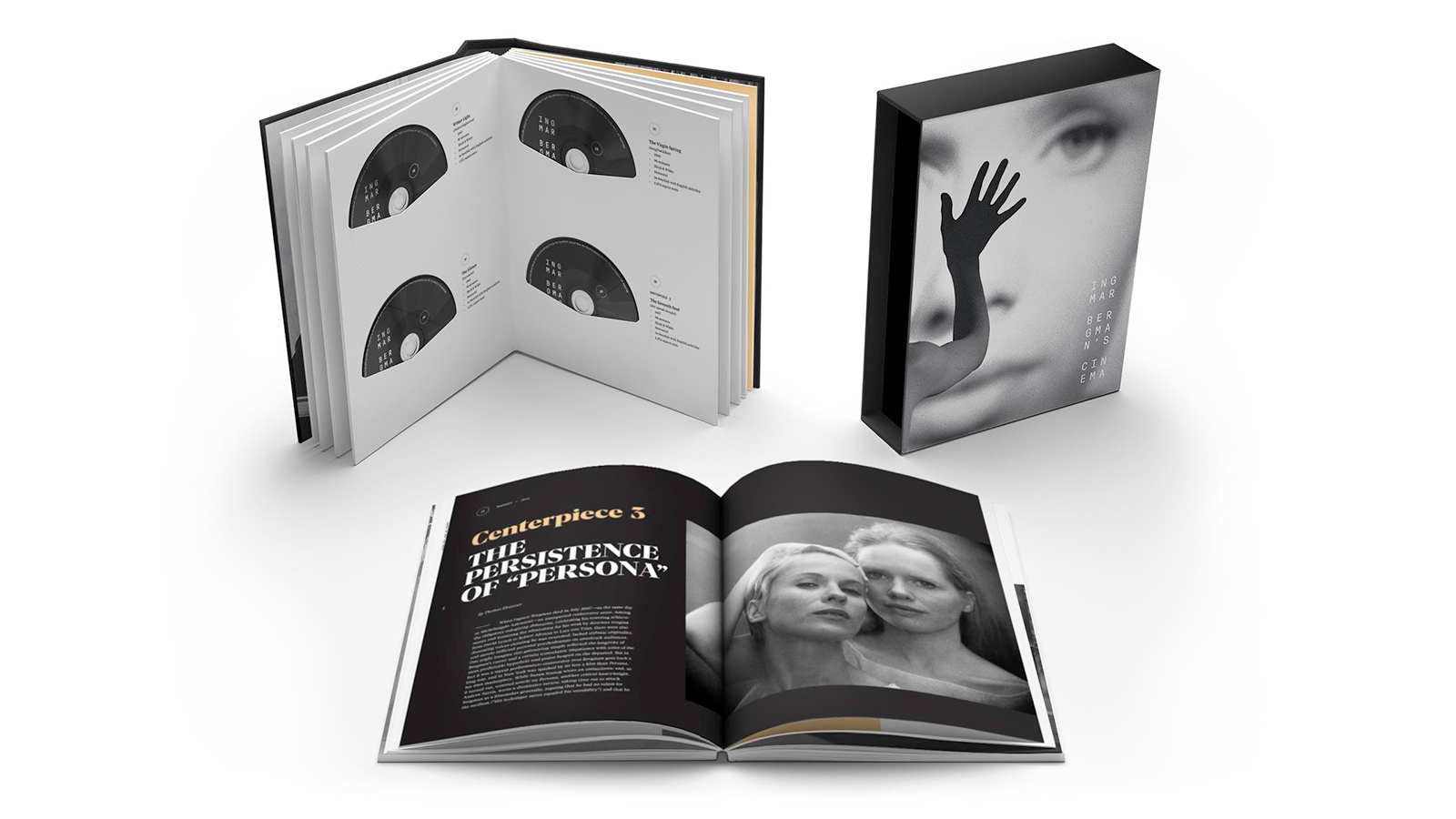

Arranged as a film festival with opening and closing nights bookending double features and centerpieces, this selection spans six decades and thirty-nine films—including such celebrated classics as The Seventh Seal, Persona, and Fanny and Alexander alongside previously unavailable works like Dreams, The Rite, and Brink of Life. Accompanied by a 248-page book with essays on each program, as well as by more than thirty hours of supplemental features, Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema traces themes and images across Bergman’s career, blazing trails through the master’s unequaled body of work for longtime fans and newcomers alike.

SPECIAL FEATURES

- Thirty-nine films, including eighteen never before released by Criterion

- Digital restorations, including a new 4K restoration of The Seventh Seal and new 2K restorations of Shame, The Touch, Waiting Women,and The Serpent’s Egg, among many others, with uncompressed monaural and stereo soundtracks

- Introductions to eleven of the films by director Ingmar Bergman

- Six audio commentaries featuring film scholars Peter Cowie and Birgitta Steene

- Over five hours of interviews with Bergman

- Interviews with many of Bergman’s key collaborators, including actors Bibi Andersson, Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Bergman, Erland Josephson, Gunnel Lindblom, Liv Ullmann, and Max von Sydow and cinematographer Sven Nykvist

- Daniel and Karin’s Face, two rarely seen documentary shorts by Bergman

- Documentaries about the making of Autumn Sonata, Fanny and Alexander, The Magic Flute, The Serpent’s Egg, The Touch, and Winter Light

- Extensive programs about Bergman’s life and work, including Bergman Island, . . . But Film Is My Mistress, Laterna Magica, Liv & Ingmar,and others

- Behind-the-scenes footage, video essays, trailers, stills galleries, and more

- PLUS: A lavishly illustrated 248-page book, featuring essays on the films by critics, scholars, and authors including Cowie, Alexander Chee, Molly Haskell, Karan Mahajan, Fernanda Solórzano, and many others; selections from Bergman’s own writing and remarks on his work; and detailed guides to the feature films and supplements included in the set

FILMS IN THIS SET

A Ship to India 1947

The hunchbacked sailor Johannes (Birger Malmsten) longs to escape his home on a salvage ship helmed by his cruel, drunken father (Holger Löwenadler)—and so does the captain himself, who is slowly going blind and planning to leave his wife and son for a music-hall performer named Sally (Gertrud Fridh). The family begins to unravel when the captain invites Sally to live on the ship, where she and Johannes form a tender connection. Told in flashback and inspired in part by French poetic realism, A Ship to India marks a major evolution in Ingmar Bergman’s early filmmaking, demonstrating his gifts as a conjurer of beguiling images and a dramatist of lacerating emotions.

Port of Call 1948

Strongly influenced by the neorealist films of Roberto Rossellini, Port of Call is Ingmar Bergman’s most naturalistic work. Shot on location in the port of Göteborg by Gunnar Fischer (who would become one of the director’s key collaborators), the film focuses on the tentative relationship between Gösta (Bengt Eklund), a sincere, easygoing seaman, and Berit (Nine‑Christine Jönsson), a suicidal young woman from a broken home. As Berit reveals more about her troubled past, and the couple confront many harsh realities in the present, a meaningful bond begins to form between them. With this confident and disciplined feature, his fifth, Bergman tackled moral and social issues head-on.

Thirst 1949

Intricately structured and technically accomplished, Thirst is an often dazzling examination of people burdened by the past and united in isolation. The principal couple, Bertil (Birger Malmsten) and Ruth (Eva Henning), travel home by train to Sweden from Switzerland, at each other’s throats the whole way. Meanwhile, in Stockholm, Bertil’s former lover, Viola (Birgit Tengroth, who also wrote the stories on which the film is based), tries to evade the predatory advances of her psychiatrist, and then of a ballet dancer who was once a friend of Ruth’s. With this dark and multilayered drama, sustained by biting dialogue, Ingmar Bergman began to reveal his profound understanding of the female psyche.

To Joy 1950

Taking its title from Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” adapted by Beethoven for his Ninth Symphony, this tragic romance opens with a violinist, Stig (Stig Olin), learning of the sudden death of his wife, Marta (Maj-Britt Nilsson). During a prolonged flashback, Stig remembers the delights and tribulations of their relationship, back to their early days in the orchestra conducted by the eminent Sönderby (Victor Sjöström), a time when Stig was riddled with self-doubt. An undeniably personal work for Ingmar Bergman, To Joy is a compelling tale of a young man’s struggle with the demons standing in the way of his happiness.

Summer Interlude 1951

Touching on many of the themes that would define the rest of his career—isolation, performance, the inescapability of the past— Ingmar Bergman’s tenth film was a gentle drift toward true mastery. Maj-Britt Nilsson beguiles as an accomplished ballet dancer haunted by her tragic youthful affair with a shy, handsome student (Birger Malmsten). Her memories of the sunny, rocky shores of Stockholm’s outer archipelago mingle with scenes from her gloomy present at the theater where she performs. A film that the director considered a creative turning point, Summer Interlude is a reverie about life and death that unites Bergman’s love of theater and cinema.

Waiting Women 1952

While at a summerhouse, awaiting their husbands’ return, a group o sisters-in-law recount stories from their respective marriages. Rakel (Anita Björk) tells of receiving a visit from a former lover (Jarl Kulle); Marta (Maj-Britt Nilsson) of agreeing to marry a painter (Birger Malmsten) only after having his child; and Karin (Eva Dahlbeck) of being stuck with her husband (Gunnar Björnstrand) in an elevator, where they talk intimately for the first time in years. Making dexterous use of flashbacks, the engaging Waiting Women is a veritable seedbed of Bergman themes, ranging from aspiring young love to the fear of loneliness, with the finale a masterpiece of chamber comedy.

Summer with Monika 1953

Inspired by the earthy eroticism of Harriet Andersson, in the first of many roles for him, Ingmar Bergman turned in this work of stunning maturity, a sensual and ravaging tale of young love. A girl (Andersson) and boy (Lars Ekborg) from working-class families in Stockholm run away from home to spend a secluded, romantic summer at the beach. Inevitably, it is not long before the pair are forced to return to reality. Although Summer with Monika was initially quietly received, its reputation gathered steam throughout the 1950s, and it became an international sensation.

Sawdust and Tinsel 1953

Ingmar Bergman presents the battle of the sexes as a ramshackle, grotesque carnival in Sawdust and Tinsel, one of the late master’s most vivid early works. The story of the charged relationship between a turn-of-the-century traveling circus owner (Ake Grönberg) and his performer girlfriend (Harriet Andersson), the film features dreamlike detours and twisted psychosexual power plays that presage the director’s Smiles of a Summer Night and The Seventh Seal, works that would soon change the landscape of art cinema forever.

A Lesson in Love 1954

One of Ingmar Bergman’s most satisfying marital comedies, A Lesson in Love stars the droll and sparkling duo of Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand as a couple deep into their married years and seeking fresh pastures. Björnstrand’s gynecologist falls for one of his patients (Yvonne Lombard), while his wife flounces off to Copenhagen to renew her fling with a sculptor (Åke Grönberg). Deftly interspersing scenes of farce with interludes of tranquil reflection, A Lesson in Love serves as an aperitif before the full-blown comic brilliance of Smiles of a Summer Night the following year.

Dreams 1955

Grave and witty by turns, Dreams develops into a probing study of the psychology of desire. Susanne (Eva Dahlbeck), head of a modeling agency, takes her protégée Doris (Harriet Andersson) to a fashion show in Göteborg, where Susanne makes contact with a former lover, and Doris finds herself pursued by a married dignitary (Gunnar Björnstrand). With its parallel narratives and subtle compositions, this film marked a transition between Ingmar Bergman’s early explorations of affairs of the heart and the more somber and virtuosic masterpieces to come later in the fifties.

Smiles of a Summer Night 1955

After fifteen films that received mostly local acclaim, the comedy Smiles of a Summer Night at last ushered in an international audience for Ingmar Bergman. In turn-of-the-century Sweden, four men and four women attempt to navigate the laws of attraction. During a weekend in the country, the women collude to force the men’s hands in matters of the heart, exposing their pretensions and insecurities along the way. Chock-full of flirtatious propositions and sharp witticisms delivered by such Swedish screen legends as Gunnar Björnstrand and Harriet Andersson, Smiles of a Summer Night is one of cinema’s great erotic comedies.

The Seventh Seal 1957

Returning exhausted from the Crusades to find medieval Sweden gripped by the Plague, a knight (Max von Sydow) suddenly comes face-to-face with the hooded figure of Death, and challenges him to a game of chess. As the fateful game progresses, and the knight and his squire encounter a gallery of outcasts from a society in despair, Bergman mounts a profound inquiry into the nature of faith and the torment of mortality. One of the most influential films of its time, The Seventh Seal is a stunning allegory of man’s search for meaning and a work of stark visual poetry.

Wild Strawberries 1957

Traveling to accept an honorary degree, Professor Isak Borg—masterfully played by the veteran filmmaker and actor Victor Sjöström—is forced to face his past, come to terms with his faults, and make peace with the inevitability of his approaching death. Through flashbacks and fantasies, dreams and nightmares, Wild Strawberries dramatizes one man’s remarkable voyage of self-discovery. This richly humane masterpiece, full of iconic imagery, is one of Ingmar Bergman’s most widely acclaimed and influential films.

Brink of Life 1958

At the height of his international acclaim, Ingmar Bergman followed two meditations on death, The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, with an examination of the mystery and pain of birth. This intimate chamber drama, set in a maternity ward, follows the emotional crises of three women as they grapple with motherhood. Another major success for the director that was also recognized for its exquisite performances by Ingrid Thulin, Eva Dahlbeck, and Bibi Andersson, Brink of Life is one of Bergman’s most brilliantly nuanced explorations of the inner lives of women.

The Magician 1958

With The Magician, an engaging, brilliantly conceived tale of chicanery that doubles as a symbolic portrait of the artist as a deceiver, Ingmar Bergman proved himself to be one of cinema’s premier illusionists. Max von Sydow stars as Dr. Vogler, a nineteenth-century traveling mesmerist and peddler of potions whose magic is put to the test in Stockholm by the cruel, eminently rational royal medical adviser Dr. Vergérus (Gunnar Björnstrand). The result is a diabolically clever battle of wits that’s both frightening and funny, shot by Gunnar Fischer in rich, gorgeously gothic black and white.

The Virgin Spring 1960

Winner of the Academy Award for best foreign-language film, Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring is a harrowing tale of faith, revenge, and savagery in medieval Sweden. With austere simplicity, the director tells the story of the rape and murder of the virgin Karin, and her father Töre’s ruthless pursuit of vengeance against the three killers. Starring Max von Sydow and photographed by the brilliant Sven Nykvist, the film is both beautiful and cruel in its depiction of a world teetering between paganism and Christianity.

The Devil’s Eye 1960

The sophisticated fantasy The Devil’s Eye—the last Ingmar Bergman film to be shot by the great Gunnar Fischer—is an engaging satire of petit bourgeois morals. The devil (Stig Järrel) suffers from an inflamed eye, which he informs Don Juan (Jarl Kulle) can be cured only if a young woman’s chastity is breached. So the legendary lover ascends from hell and sets about seducing an innocent pastor’s daughter, Britt-Marie (Bibi Andersson). Bergman’s dialogue bubbles with an irony reminiscent of his beloved Molière, and the music of Domenico Scarlatti (performed by Bergman’s fourth wife, Käbi Laretei) underscores the joy that infuses much of the film.

Through a Glass Darkly 1961

While vacationing on a remote island retreat, a family’s fragile ties are tested when daughter Karin (an astonishing Harriet Andersson) discovers her father (Gunnar Björnstrand) has been using her schizophrenia for his own literary ends. As she drifts in and out of lucidity, Karin’s father, her husband (Max von Sydow), and her younger brother (Lars Passgård) are unable to prevent her descent into the abyss of mental illness. Winner of the Academy Award for best foreign-language film, Through a Glass Darkly, the first work in Ingmar Bergman’s trilogy on faith and its loss (to be followed by Winter Light and The Silence), presents an unflinching vision of a family’s near disintegration and a tortured psyche further taunted by the intangibility of God’s presence.

Winter Light 1963

“God, why hast thou forsaken me?” With Winter Light, Ingmar Bergman explores the search for redemption in a meaningless existence. Small-town pastor Tomas Ericsson (Gunnar Björnstrand) performs his duties mechanically before a dwindling congregation, including his stubbornly devoted lover, Märta (Ingrid Thulin). When he is asked to assuage a troubled parishioner’s (Max von Sydow) debilitating fear of nuclear annihilation, Tomas is terrified to find that he can provide nothing but his own doubt. The beautifully photographed Winter Light is an unsettling look at the human craving for personal validation in a world seemingly abandoned by God.

The Silence 1963

Two sisters—the sickly, intellectual Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and the sensual, pragmatic Anna (Gunnel Lindblom)—travel by train with Anna’s young son, Johan (Jörgen Lindström), to a foreign country that appears to be on the brink of war. Attempting to cope with their alien surroundings, each sister is left to her own vices while they vie for Johan’s affection, and in so doing sabotage what little remains of their relationship. Regarded as one of the most sexually provocative films of its day, Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence offers a disturbing vision of emotional isolation in a suffocating spiritual void.

All These Women 1964

Conceived as an amusing diversion in the wake of Ingmar Bergman’s despairing trilogy, this comedy is the director’s first film in color, and it is an opulent visual feast. Working from a bawdy screenplay he cowrote with actor Erland Josephson, about a supercilious critic drawn into the dizzying orbit of a famous cellist, Bergman brings together buoyant comic turns by a number of his frequent collaborators, including Jarl Kulle, Eva Dahlbeck, Harriet Andersson, and Bibi Andersson. All These Women, in which Bergman pokes fun at the pretensions of drawing-room art, possesses a distinctly playful atmosphere and carefree cadences.

Persona 1966

By the midsixties, Ingmar Bergman had already conjured many of the cinema’s most unforgettable images. But with the radical Persona, he attained new levels of visual poetry. In the first of a series of legendary performances for Bergman, Liv Ullmann plays a stage actor who has inexplicably gone mute; an equally mesmerizing Bibi Andersson is the garrulous young nurse caring for her in a remote island cottage. While isolated together there, the women undergo a mysterious spiritual and emotional transference. Performed with astonishing nuance and shot in stark contrast and soft light by Sven Nykvist, the influential Persona is a penetrating, dreamlike work of profound psychological depth.

Hour of the Wolf 1968

The strangest and most disturbing of the films Ingmar Bergman shot on the island of Fårö, Hour of the Wolf stars Max von Sydow as a haunted painter living in voluntary exile with his wife (Liv Ullmann). When the couple are invited to a nearby castle for dinner, things start to go wrong with a vengeance, as a coven of sinister aristocrats hastens the artist’s psychological deterioration. This gripping film is charged with a nightmarish power rare in the Bergman canon, and contains dreamlike effects that brilliantly underscore the tale’s horrific elements.

Shame 1968

Shame was both Ingmar Bergman’s examination of the violent legacy of World War II and his scathing response to the escalation of the conflict in Vietnam. Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann star as musicians living in quiet retreat on a remote island farm, until the civil war that drove them from the city catches up with them there. Amid the chaos of the military struggle, vividly evoked by pyrotechnics and by Sven Nykvist’s handheld camera work, the two are faced with uncomfortable moral choices. This film, which contains some of the greatest scenes in Bergman’s oeuvre, shows the devastating impact of war on individual lives.

The Rite 1969

Ingmar Bergman conceived this experimental work as a response to his controversial tenure at the Royal Dramatic Theatre. Focusing on four characters—a trio of actors charged with obscenity (Ingrid Thulin, Gunnar Björnstrand, Anders Ek), and the judge assigned to try them (Erik Hell)—The Rite alternates between criminal interrogations and interpersonal confrontations shown in flashback, leading to a final “performance” that makes for one of the most bizarre moments in Bergman’s filmography. Staged on bare sets and shot almost entirely in close-up, The Rite condenses a decade’s worth of cinematic exploration into seventy-five tense, unsettling minutes.

The Passion of Anna 1969

This drama shot on Ingmar Bergman’s beloved Fårö island describes a mood of fear, isolation, and the longing for connection. Not long after the dissolution of his marriage and a fleeting liaison with a neighbor (Bibi Andersson), the reclusive Andreas (Max von Sydow) begins an ill-fated affair with the mysterious, beguiling Anna (Liv Ullmann), who has recently lost her own husband and son. Bergman’s first color film since All These Women, The Passion of Anna is a sequel of sorts to Shame. It incorporates documentary-style interviews with the actors, blurring the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, lies and truth, dreams and reality, identity and anonymity.

Fårö Document 1970

Ingmar Bergman had discovered the bleak, windswept Fårö while scouting locations for Through a Glass Darkly in 1960. Nearly a decade later—and after shooting a number of arresting dramas there and making the island his primary residence—the director set out to pay tribute to its inhabitants. In Fårö Document, shot on handheld 16 mm by Sven Nykvist, Bergman interviews a variety of locals, in the process laying bare the generational divide between young residents eager to leave the island and older people more deeply rooted in bucolic tradition. The film revealed Bergman to be a sensitive and masterly documentarian.

The Touch 1971

With his first English-language film, a critical and box-office disaster, Ingmar Bergman delivered a compelling portrait of conflicting desires. In The Touch, a chance encounter between seemingly contented housewife Karin (Bibi Andersson) and David (Elliott Gould), an intense American archaeologist scarred by his family’s past, leads to the initiation of a torrid and tempestuous affair, one that eventually threatens the stability of Karin’s marriage to a respected local surgeon (Max von Sydow). Upon its release, the filmmaker declared this emotionally complex and sensitively performed film to be his first real love story.

Cries and Whispers 1972

This existential wail of a drama concerns two sisters, Karin (Ingrid Thulin) and Maria (Liv Ullmann), keeping vigil for a third, Agnes (Harriet Andersson), who is dying of cancer and can find solace only in the arms of a beatific servant (Kari Sylwan). An intensely felt film that is one of Bergman’s most striking formal experiments, Cries and Whispers (which won an Oscar for the extraordinary color photography by Sven Nykvist) is a powerful depiction of human behavior in the face of death, positioned on the borders between reality and nightmare, tranquility and terror.

Scenes from a Marriage 1973

Scenes from a Marriage chronicles the many years of love and turmoil that bind Marianne (Liv Ullmann) and Johan (Erland Josephson), tracking their relationship as it progresses through a number of successive stages: matrimony, infidelity, divorce, and subsequent partnerships. Originally conceived as a five-hour, six-part television miniseries, the film is also presented in its three-hour theatrical cut. Shot on 16 mm in intense, intimate close-ups by cinematographer Sven Nykvist and featuring flawless performances by Ullmann and Josephson, Bergman’s emotional X-ray reveals the intense joys and pains of a complex bond.

The Magic Flute 1975

This scintillating screen version of Mozart’s beloved opera shows Bergman’s deep knowledge of music and his gift for expressing it in filmic terms. Casting some of Europe’s finest soloists—among them Josef Köstlinger, Ulrik Cold, and Håkan Hagegård—the director lovingly recreated the baroque theater of the Drottningholm Palace in Stockholm to stage the story of the prince Tamino (Köstlinger) and his zestful sidekick Papageno (Hagegård), who seek to save a beautiful princess (Irma Urrila) from the clutches of evil. A celebration of love, forgiveness, and the brotherhood of man, The Magic Flute is considered by many to be the most exquisite opera film ever made.

The Serpent’s Egg 1977

One rainy night in Weimar Berlin, Jewish American circus performer Abel Rosenberg (David Carradine) discovers that his brother Max, his trapeze-act partner, has killed himself. What follows is one of Bergman’s darkest and most fearful visions, as the drowned-in-drink Abel and Max’s ex-wife, cabaret singer Manuela (Liv Ullmann), feel increasingly unwelcome in a menacing and destitute city, eyed by the police as well as a scientist with diabolical intentions. The director’s sole big-budget Hollywood production, for which he created a surreal and atmospheric Berlin on a Munich soundstage, The Serpent’s Egg conjures a Kafkaesque nightmare about the decaying society that gave rise to the horrors of Nazism.

Autumn Sonata 1978

Autumn Sonata was the only collaboration between cinema’s two great Bergmans: Ingmar and Ingrid, the monumental star of Casablanca.The grande dame, playing an icy concert pianist, is matched beat for beat in ferocity by the filmmaker’s recurring lead Liv Ullmann, as her eldest daughter. Over the course of a day and a long, painful night that the two spend together after an extended separation, they finally confront the bitter discord of their relationship. This cathartic pas de deux, evocatively shot in burnished harvest colors, ranks among the director’s major dramatic works.

Fårö Document 1979 1979

Midway through his time in Germany, Bergman returned to Fårö for his second documentary exploration of the remote Swedish island he loved and the socioeconomic realities experienced by those who lived there. Longer, more optimistic, and less ascetic than its predecessor, this film charts a calendar year in the life of the island’s 673 inhabitants, many of whom he observes working tirelessly shearing sheep, thatching roofs, and slaughtering livestock, as well as going about various communal rituals. Distilled from twenty-eight hours of material, Fårö Document 1979 is a lyrical depiction of life’s cyclical nature.

From the Life of the Marionettes 1980

Made during his self-imposed exile in Germany, Ingmar Bergman’s From the Life of the Marionettes offers a lacerating portrait of a destructive marriage and a complex psychological analysis of a murder. Businessman Peter nurses fantasies of killing his wife, Katarina, until a prostitute becomes his surrogate prey. In the aftermath of the crime, Peter and Katarina’s psychiatrist and others attempt to explain its roots. Jumping back and forth in time, this compelling film moves seamlessly between seduction and repulsion, and the German cast is superb.

Fanny and Alexander – The Theatrical Version 1982

Through the eyes of ten-year-old Alexander, we witness the delights and conflicts of the Ekdahl family, a sprawling bourgeois clan in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Sweden. Ingmar Bergman intended Fanny and Alexander as his swan song, and it is the director’s warmest and most autobiographical film, an Academy Award–winning triumph that combines his trademark melancholy and emotional intensity with immense joy and sensuality. Bergman described Fanny and Alexander as “the sum total of my life as a filmmaker.”

Fanny and Alexander – The Television Version 1983

Through the eyes of ten-year-old Alexander, we witness the delights and conflicts of the Ekdahl family, a sprawling bourgeois clan in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Sweden. Ingmar Bergman intended Fanny and Alexander as his swan song, and it is the director’s warmest and most autobiographical film, an Academy Award–winning triumph that combines his trademark melancholy and emotional intensity with immense joy and sensuality. Bergman described Fanny and Alexander, presented here in both the theatrical and the five-hour television versions, as “the sum total of my life as a filmmaker.” And in this, the full-length (312-minute) version of his triumphant valediction, his vision is expressed at its fullest.

After the Rehearsal 1984

With this spare chamber piece, set in an empty theater, Ingmar Bergman returned to his perennial theme of the permeability of life and art. Lingering after a rehearsal for August Strindberg’s A Dream Play (a touchstone for the filmmaker throughout his career), eminent director Henrik (Erland Josephson) enters into a frank and flirtatious conversation with his up-and-coming star, Anna (Lena Olin), leading him to recall his affair with Anna’s late mother, the self-destructive actress Rakel (Ingrid Thulin). The sharply written and impeccably performed After the Rehearsal, originally made for television, pares away all artifice to examine both the allure and the cost of a life in the theater.

Saraband 2003

With his final film, Ingmar Bergman returned to two of his most richly drawn characters: Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Liv Ullman), the couple from Scenes from a Marriage. Dropping in on Johan’s secluded country house after decades of separation, Marianne reconnects with the man she once loved. Nearby, the widowed musician Henrik (Börje Ahlstedt), Johan’s son from an earlier marriage, clutches desperately to his only child, the teenage Karin (Julia Dufvenius). A chamber piece performed by four wounded characters and suffused with disappointment and forgiveness, Saraband is a generous farewell to cinema from one of its greatest artists.